How funds are flagged, reported, safeguarded, and ultimately returned

Every year, large volumes of financial assets are separated from their owners and reported to the state for safekeeping. Here’s the life cycle of an unclaimed asset—from the moment an account goes quiet to the day a rightful owner (or heir) is paid.

When does property become “unclaimed”?

An asset is treated as unclaimed when there’s been no owner-initiated activity or contact for a legally defined dormancy period. The exact window depends on the asset type and state law, but it commonly ranges from 1–5 years (shorter for wages; longer for some insurance proceeds and securities).

“Owner activity” generally includes actions like logging in, making a deposit/withdrawal, cashing a check, updating contact details, or responding to a notice. Merely accruing interest or fees usually does not count as owner activity.

What holders must do before reporting (due diligence)

Before classifying funds as abandoned, the holder—such as a bank, insurer, employer, transfer agent, or utility—must perform due diligence, which typically includes:

- Sending a written notice to the last known address (and, where permitted, email).

- Allowing reasonable time for the owner to respond.

- Recording the attempt and any returned-mail codes.

If contact still fails and there’s been no qualifying activity during the dormancy period, the holder proceeds to report.

How assets are reported and transferred

Reporting happens on a statutory schedule (often annually):

- Create the report

The holder compiles a file listing the owner’s name, last known address, tax ID (if on file), property type and value, and the date of last activity.

- Submit & remit

The report is filed with the state unclaimed-property program; the asset (or its cash equivalent) is remitted for custody.

- Cash & deposits: transferred as cash.

- Securities: some states accept shares in kind; others require liquidation and transfer of proceeds.

- Safe-deposit contents: inventoried, then transferred; many states auction tangible items later and credit the proceeds to the owner’s record.

- State custody begins

The state becomes custodian—not owner—until a valid claim is approved.

Safeguarding in state custody

Once received, property is recorded, safeguarded, and searchable:

- Records & searchability: The state creates/updates a record so owners (or heirs) can find it through public search tools.

- Funds handling: Cash is held in pooled or interest-bearing accounts per state policy. Tangible items are secured; if auctioned, net proceeds are preserved on the owner’s record.

- No forfeiture of rights: Custody is designed to preserve access, not eliminate it. Owners (or heirs) can typically claim at any time.

What it means for owners and heirs

- You retain the right to claim. States act as custodians until you verify entitlement.

- You’ll be paid by the state. After approval, the state issues payment (check or ACH where available) to the rightful claimant.

- Documentation matters. Standard claims require a government ID and proof of current address; estates/trusts may require probate or authority documents. For name changes, include supporting records.

Tip: If you see an unfamiliar company name on a listing, remember that mergers, servicers, or brand changes are common. The state record reflects the holder that reported the asset at the time.

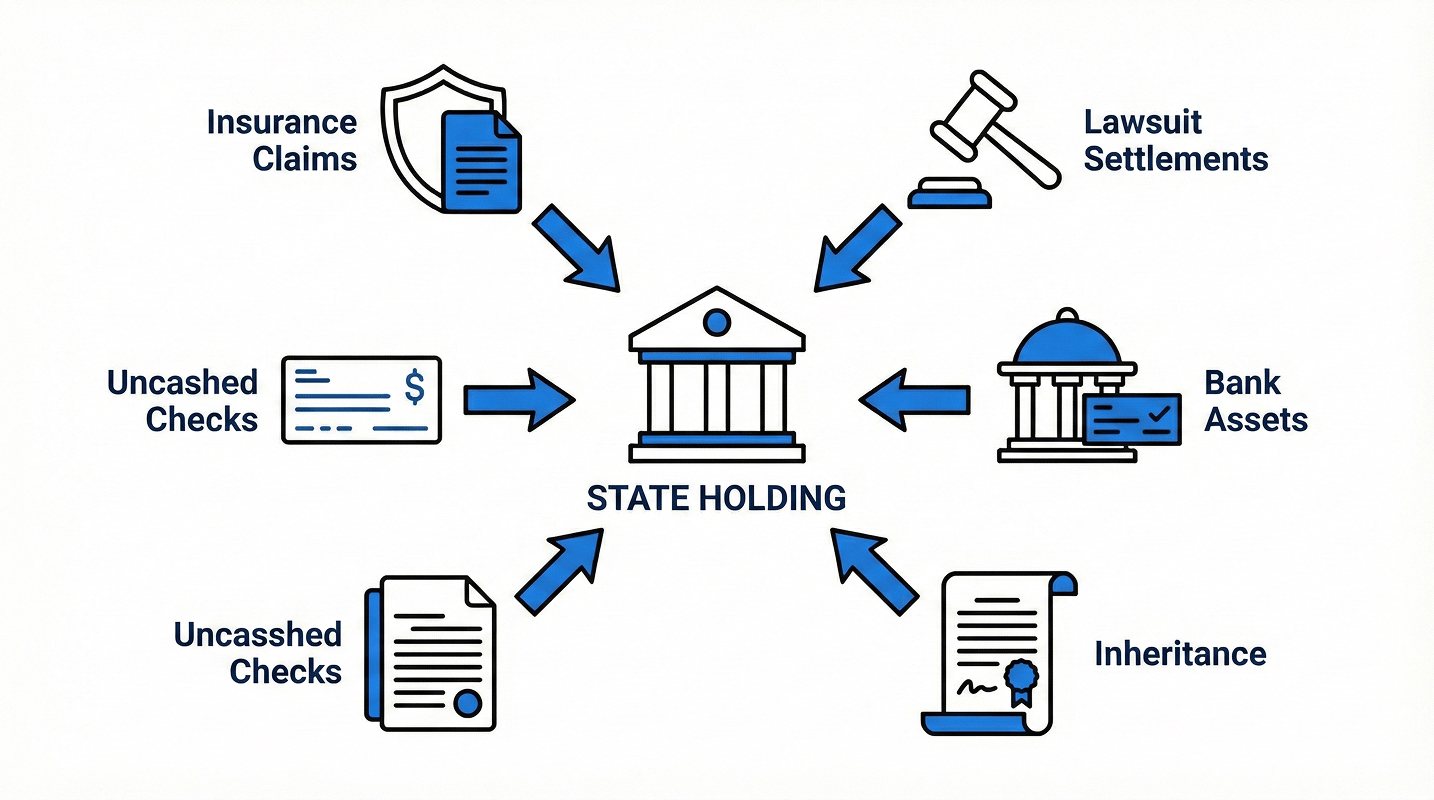

Common property types that get reported

- Dormant bank/credit-union accounts (checking, savings, CDs)

- Uncashed checks (payroll, refunds, rebates, vendor payments)

- Insurance proceeds (life, premium refunds) and annuities

- Brokerage/securities (dividends, shares, residuals)

- Utility and rental deposits; escrow balances

- Trust and fiduciary disbursements

- Safe-deposit box contents (tangible property)

If no claim is made

Funds remain in custody indefinitely (or as allowed by state law). Many states do not impose a time limit on owners or heirs to come forward. If tangible property is sold, proceeds remain credited to your record and are claimable.

A typical timeline (illustrative)

- Dormancy period runs (e.g., 1–5 years, depending on property type/state).

- Due-diligence notice sent by the holder to the last known address/email.

- Report & remit to the state on the statutory cycle.

- State custody & listing—property appears in public search tools.

- Owner/heir files a claim with ID and required documents.

- State review (may request clarifications).

- Payment issued by the state upon approval.

Myths vs. reality

- “The state keeps my money.”

No—the state holds it as custodian. Your entitlement generally doesn’t expire.

- “Interest keeps accruing while in custody.”

Not necessarily. Policies vary; some states do not credit interest during custody. The key benefit is preservation and access, not investment return.

- “If I never got a letter, I don’t have funds.”

Not true. Bad addresses, spam filters, and returned mail are common. Many owners discover funds only after searching.

How to keep assets from going unclaimed

- Update contact info with every bank, insurer, employer, and brokerage after moves or name changes.

- Consolidate small/duplicate accounts where practical.

- Enable alerts and review statements quarterly.

- Tell a trusted person where key account/policy records live.

Summary

When accounts go quiet and outreach fails, holders are required to report and transfer assets to state custody. There, the property is secured, recorded, and made findable until a verified owner (or heir) claims it. The system exists to protect access, not to take ownership—so if your name appears on a listing, the path is open to get it back.